Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Email | RSS

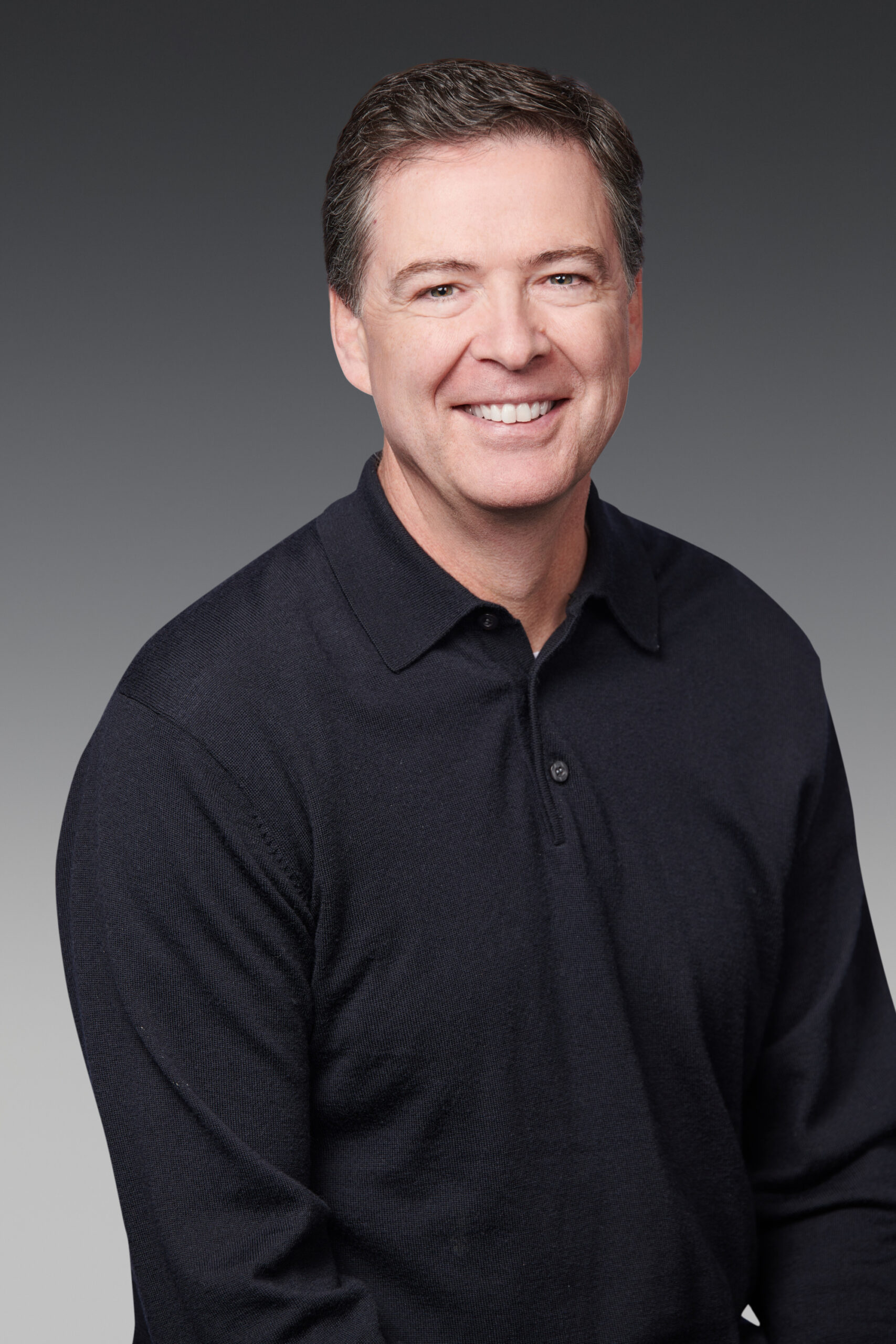

Ep. 3 — A Home Invasion Trauma Leads to a Law Enforcement Career / James Comey, Former Director, Federal Bureau of Investigation

In this episode, James Comey describes how, as a high school senior, he and his brother were held at gunpoint in their New Jersey home by a serial rapist and robber and how that confrontation with death ultimately influenced his decision to go into law enforcement.

Comey talks about how attending a bail hearing in a Mafia case as a young law clerk in New York convinced him to become a federal prosecutor and help bring down some of the most powerful Mafia families in Gotham.

He then shares stories of how his experience in dealing with the Mafia helped him understand and deal with President Donald Trump. Comey has testified under oath that Trump first sought to secure his blind loyalty, and when Comey refused, fired him as the FBI Director in an attempt to shut down the Bureau’s investigation into the Russian interference in the 2016 Democratic election.

Comey also shares his views on the Special Counsel’s final report on the Russian interference. He discusses his handling of the Hillary Clinton email investigation, which many attribute to Clinton’s loss in the 2016 Presidential race. And he describes how he learned the greatest leadership in life from a personal tragedy.

Transcript

Chitra: Hello and welcome to When It Mattered. I’m your host Chitra Ragavan. I’m also the founder and CEO of Goodstory Consulting, an advisory firm helping technology startups find their narrative. On this weekly podcast we invite leaders from around the world to share one personal story that changed the course of their life and work, and how they lead and deal with adversity. Through these stories, we take you behind the scenes to get an inside perspective of some of the most eventful moments of our time.

Chitra: On this episode, we will be talking to James B. Comey. He has spent four decades in law as a federal prosecutor, a business lawyer, and working closely with three US Presidents. We served as Deputy Attorney General under President George W. Bush. In September 2013, President Barack Obama appointed Comey as the seventh director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. In that role, Comey came under fire for his handling of the bureau’s investigation into the Hillary Clinton email controversy in the lead-up to the 2016 US elections. Comey’s 10 year term was cut short in May 2017 when President Donald Trump summarily fired him as the FBI Director. Statements from the president and the White House indicated that the firing was intended to ease the pressure over the FBI’s investigation of the Russian interference in the 2016 US elections. Comey currently teaches ethical leadership at William & Mary College and is the author of the book Higher Loyalty. Jim, welcome to the podcast.

James: It’s great to be with you, Chitra.

Chitra: Tell us a little bit about your background and how you got into law and law enforcement.

James: Well, I was a science focused kid in high school and thought that I would become a doctor. Looking back through the lens of now as an old person, I think an event that happened to me as a senior in high school steered me in a way that even I couldn’t see at the time. A serial rapist and robber kicked in my parent’s front door one night at their home in Northern New Jersey and ended up in a terrifying evening holding me and my brother captive. We escaped, he caught us again, and at least twice during that night I thought he was going to kill us, and that had an enormous effect on me. It helped give me some perspective on life that was useful, as painful as it was, and I think again, without me even knowing, it steered me in a way towards law enforcement and thinking about what victims experienced. I still thought I was going to be a doctor, and then figured out that wasn’t for me late in my college career about three years later.

Chitra: What happened?

James: Well, I first took a class called Death, and the experience of that night at my parent, lying in my parent’s bed thinking I was about to be killed had brought kind of a darkness to me as a young person and an obsession understandably with death. I was a chemistry major walking through the chem building one day and I didn’t know it shared space with the religion department, and I saw the word death on a bulletin board and so I stopped, and it turns out it was a course offering and the professor, who became a friend of mine said most places call that death and dying, but he thought that was too depressing, so he called it death. I signed up for death and it changed my life. My subject was interesting, but I got introduced to the ethicist in the religion department, a guy named Hans Tiefel, and gradually through interacting with him and the readings we did, I came to realize, you know what? Given my strengths and weaknesses, I can be more useful to people as a lawyer than as a doctor. So I doubled majored in chemistry and religion, and at the end of my junior year switched and decided to take the LSAT and apply to law school.

Chitra: When you got out of law school, you didn’t know what type of lawyer you wanted to be till you attended a court case dealing with the mafia. What was the case and why did it have such an impact on you?

James: Yeah, all I knew is that I wanted to help people, and I represented poor people in a clinic in law school and loved that work, but I went to clerk for a federal judge in Manhattan, and he would let us sit in the courtroom if cool stuff was going on, and what was going on didn’t seem cool on the face of it, it was just a bail hearing, but it was more than just a bail hearing. It was the government trying to use a brand new statute from congress to hold without bail the boss of the Genovese crime family, one of the five New York mafia families, and the guy’s name was Anthony Salerno, nicknamed Fat Tony, and I was a 25 or a 26 year old sitting in the empty jury box, watching as two young prosecutors, not much older than I, presented the case that Fat Tony was a danger to the community, and they had tapes from under his table at the Palma Boys Social Club in East Harlem, which was then a mob enclave, and on the tapes Fat Tony was walking about breaking people’s legs and whacking people, and I sat there listening to this and looking at Fat Tony, who was out of central casting.

James: He was fat, the nickname was accurate, but he had this bald head, unlit stogy in his mouth, walked with a cane and he spoke with this gravely voice that he would use when his lawyer wasn’t doing as good a job as he needed him to do, and so he would shout out occasionally, “That’s an outrage, your honor.” And so I’m watching this and I think it’s the coolest thing I’ve ever seen. The other defendant in the case was a guy named Vincent The Fish Cafaro, who looked like a fish. And so I was so fired up. I went home and called my girlfriend, now my amazing wife, and I said, “I know what I want to do with my life. I want to be a federal prosecutor.” And she said, “What’s that.” I explained and I said, “And I want to do it here in New York.” Where Rudy Giuliani was then the US Attorney, and that was a much longer conversation with my wife, who hated New York. That’s how it started.

Chitra: Fascinating, but before you became a federal prosecutor in the Southern District, you spent a year in Madison, Wisconsin in a big law firm, and most lawyers tend to hate the big law firm experience. But you say that you really liked it a lot. Why was that?

James: Yeah, I know it sounds crazy to say I enjoyed my year at a big soul sucking law firm, and the reason I enjoyed it is they sent me on an assignment, that again, didn’t seem real cool, to work as a very junior person on an insurance litigation in Madison, Wisconsin, and I spent almost an entire year, my year in private practice there, and what was amazing about it and life altering was I got to meet the local council who the big firm had hired to help us navigate the local courts with a case that’s pending, and his name was Dick Cates, and he was a great person, a great lawyer, a great leader, a great father, a great grandfather, a great husband, and I learned more from just watching that person live, he never gave me any speeches. He just showed me what it was to balance work and life, what it was to find joy in people’s stories and in the absurdities of life. What it was to be someone who lived life to the fullest but never took yourself seriously, and could laugh at your own mistakes and laugh at other people’s pomposity.

James: Dick Cates was a brilliant lawyer who could’ve gone to work in a big city at a big law firm, but didn’t want to do that. He wanted to ride his bike to work and move his children to a farm so they didn’t get soft. So he had five kids, which coincidentally is what I ended up with, and he raised them on a farm, he biked to work, he had his own law firm, he took anybody as a client, whether they could pay or not, and he lived an incredibly rich life, although he never made the money that rich people at big law firms make, and that, I talk about the term I use is life plagiarism. I decided I’m going to copy Dick Cates’ life, and it’s been imperfect, but it’s been a goal to be like Dick Cates for most of my life.

Chitra: So then you moved to the Southern District of New York, some call it the Sovereign District of New York because of its reach and power of the federal prosecutor there, and you worked under Rudy Giuliani who was somewhat of an antithesis of Dick Cates.

James: Yes, he was. Rudy was an imperial style leader who was not great then, or I don’t think great now at laughing at himself, at taking joy in the stories of other, of taking joy in launching and developing others, which requires a certain humility because you’re not the star, this young person you’re helping in the star. And so I saw a very different style. I don’t think I realized then how different it was because I was fired up to work for Rudy, right? We were knocking down doors, we thought of the world as our venue. Did it happen on the Earth? If it did, we can reach it from the Southern District of New York. I really liked working there and didn’t realize what was missing in his leadership style until I tried to lead down the road.

Chitra: So then you started cutting your prosecutorial teeth on some of these mafia cases like the ones you saw when you just got out of law school, and one of your big early victories was against the Gambino crime family, one of the biggest crime families in the US. What lessons did you learn from those criminals and from mob informants that you had to try and flip like Sammy the Bull Gravano who was the highest ranking mafioso to flip on his family.

James: Yep. Sammy the Bull was the number two in the Gambino crime family, the underboss, and a person who had been engaged in a lot of crime and violence, and like all of these characters, and I guess maybe like humans in general, would tell himself stories to offer his existence meaning and purpose and to explain it. He did terrible things, but it was as part of a venture that was his life, and he only did it because the boss ordered him to do it. So I learned early on that people tell themselves stories to justify, and if you can’t convince yourself, who can you convince? We had Sicilian Mafia killers who were our witnesses, and they would say the same thing, that they joined Cosa Nostra because without it, they were nobodies, and yeah they did terrible things, but they did it as part of this structure which they were a part, and some of them thought that it gave them meaning, and the second thing I learned is there are leadership lessons to be drawn from mafia families.

James: There’s a leadership culture in a mafia family. I didn’t realize how relevant that leadership culture, seeing it was going to be to the rest of my career, but there is a structure. There is a boss, there’s an underboss, there’s a consigliere, kind of like the general counsel. The there are captains, and soldiers, there’s a structure, and on top of that structure is a culture, which is the way things are really done around here, and it was really interesting to see it and then to see it again throughout my career.

Chitra: I will come to that a little bit later. One of the themes that resonates throughout your life and through the book that you’ve written, A Higher Loyalty, is the idea of bullying and bullies. The mafia crime bosses were just one example of that, but it’s hard to imagine. You’re six foot eight but you were bullied as a child you say, and when you were a little older you did some bullying of your own, and those taught you some lessons too.

James: Yep. I was not a big kid. I had a big mouth but it was mismatched with my flabby small body, and so yeah, I got picked on a lot when I was in junior high school and then early in high school, and it caused me a lot of pain. I think it was good for me in a lot of ways. It developed my ability to assess situations and people, to sense danger, and to evaluate quickly in a situation, but yeah, I then got to college and I participated with a group of other boys in harassing and bullying another buy, and the lesson I learned from that is the danger and the power of groups. I wanted to belong, and if there’s anyone alive who knew that bullying was wrong it was I. I grew up in a household, my mother used to say all the time, “Don’t follow the crowd. If they’re lining up to jump off the George Washington Bridge, are you just going to get in line?” And so I was fiercely proud of my independence and the lessons I’d learned from being bullied, and then I joined a group and bullied a kid. How could I possibly do that?

James: So we actually talk about it in the classes I teach now. The power of groups to convince ourselves that we should surrender our moral authority to the group. The group’s making decisions, when we truth is the group has no brain, but we go along because we fear what it might do to us if we don’t, and we like the affirmation of being part of a group. So those two experiences, being bullied and bullying, I’m ashamed of the second one, but it was a searing lesson to never forget the power and the danger of human groups.

Chitra: Some of the other lessons, probably one of the biggest lessons you learned in leadership came as you got a little older, you married, you had children. What was that profound lesson that you learned?

James: Through tragedy. My wife Patrice and I had a baby boy, Collin, who was born, it was our fourth child and was born healthy, healthy baby boy and he died nine days later of a preventable bacterial infection, and we didn’t know it at the time but we found out pretty quickly that we were the victim of the American medical practices turning too slowly. About a quarter of all women carry naturally a bacteria called group B streptococcus, it doesn’t hurt them but it can kill their babies. Babies are exposed during delivery, it’s easily tested for and easily treated during delivery, but not all of American docs or hospitals were doing this in 1995, and we happened to live in a place, Richmond Virginia, where the hospital didn’t make all the doctors test. So Patrice wasn’t tested, our baby wasn’t treated during delivery, and he died nine days later. So look, I tell that story, obviously that’s an incredibly important part of my life and my family, but I talk about it in the book because watching what my wife did next taught me the most important leadership lesson I’ve ever learned.

James: She was broken hearted. Her pain was increased when we learned this was preventable and she said, “You know what? I can’t bring my son back. I can’t ever justify what just happened to us, but if I’m going to go on living, I must find some good to follow this.” Again, not to justify it, but because that’s what it means to go on living. I can’t let evil hold the field, and so I will make good follow this, and she and a group of other mothers and medical professionals worked, and worked, and worked, and pushed to make the entire country turn. So if you’ve had a baby or you know someone who’s had a baby in the last 15, 20 years, everywhere in the United States, they’ve been tested for group B strep and those babies have lived. If she were here, she would be quick to say that it doesn’t ever fill the hole in my heart, but that’s what it means to take bad things happening to good people and reframe it in a way that can offer you purpose and meaning going forward.

James: The reason it was so useful to me is by total fluke I got sent to Manhattan right after 9/11 as the US Attorney, and I had to stand on a pit at Ground Zero and try to offer some sense of meaning and purpose to people whose loved ones had literally disappeared. I mean, it’s so hard sometimes to conjure the how we all felt at that time, but hundreds of human beings disappeared that day in Lower Manhattan and no trace of them were ever found ever, and how do you speak to those people? And so I spoke to them channeling Patrice. I said, “I can’t explain your loss, I can’t make it worth anything, but I can tell you what our obligation is. If we’re still going to go on living. We have to make good follow this. Not again, to outweigh it or to make it worth it, but because that’s what it means to remain a person alive and to seek meaning in your life.” And so I talked about ways in which we were all trying to make people safer, better, comfort the wounded in ways that would offer us an opportunity for good going forward.

James: So that’s why that story is in my book, and that’s why it’s so important to me.

Chitra: And with baby Collin you had to make the very painful decision to take him off life support. Having made that decision, was every other decision in your life easier?

James: Yeah, I mean, my kids who are here, they would groan because they’ve heard me say so many times in difficult situations, look, nobody is going to die, well that day someone body was going to die, and so it makes all other decisions easy. Now look, it was inevitable. I mean, the damage to his brain was so extraordinary that he wasn’t going to be able to live off the machine, but still be idea of being parents making that decision is something you don’t ever get over and everything else pales in comparison.

Chitra: One of the other themes that runs through your book, in your life and your career has to do with this nature of lies and deception, and you come to some conclusions about lying from your own experience and watching others lie. Can you talk a little bit about that?

James: Yeah, everybody lies. If you’re listening to this, you probably lied about something today. Someone asked you, “Do my shoes look nice?” Or, “Do you think it’s too hot in here?” You may lie, and that’s okay. Everybody lies, the question is what do you lie about, when, to whom, and what do you do about it if you find yourself telling a lie that matters? And so I’ve lied plenty in my life. I’ve tried not to lie about important things. I remember when I was a kid, not a kid, I was a law student and people would assume that I’d played basketball in college when I hadn’t. I’d grown too late, but it was a sore point for me and I just didn’t want to explain to a bunch of strangers that I grew too late, that I hurt my knee, and blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, and so I would just let them assume that I played, and with some of them I affirmatively said, “Yeah, yeah. I played in college.” And I know it may seem silly to people, but that ate at me, ate at me, and I went back and tried to fix it with people years later that I had said that to and it was another lesson.

James: I consider myself a good person. I not only lied, I lied about something that matter to me in a way that I knew people relied on. So it’s a cautionary tale that none of us should be on too high a horse, but that we have to remember it’s what you lie about, to whom, when, and what do you do about it when you do something you shouldn’t do.

Chitra: Some of your highest profile cases had to do with going after people, prosecuting people who lied, and in some cases you were criticized that they, Martha Stewart was one, Scooter Libby. The criticism was these people had committed relatively small offenses compared to the other people who had done much worse. Why did you go after them?

James: Yeah, people used to say, “Well, these are just process crimes.” Martha Stewart lied during an investigation of insider tradings, Scooter Libby who was the vice president’s chief of staff lied during an investigation of a disclosure of a, the identity of an undercover CIA officer. These are just process crimes and my response would be in a sense, but the process we’re talking about is the rule of law in the United States, which depends upon an honor system, that people will tell the truth when they’re asked questions, that they’ll produce documents that may hurt them when they get a subpoena, and the nature of honor systems is they only work if people fear not honoring the obligation, and so if you can prove beyond a reasonable doubt that someone lied during an investigation, or destroyed or withheld documents, you have to prosecute those cases. Not because Martha Stewart is a mob boss, but because the system requires enforcement of those who violate the honor code that’s at the heart of it and the punishment is what should drive, should match the magnitude of the offense. Martha Stewart went to jail for five months as I recall, that was fine by me. Bringing the case mattered, and the department of justice brings about 2,000 of those cases every year because folks lie, but if you don’t enforce those, pretty soon everybody is going to be lying.

James: Used to be a time when people who took an oath in the name of god feared going to hell if they lied. That fear has slipped away from us, and so they must fear the prosecutor.

Chitra: Your book is called A Higher Loyalty. How did you come up with that name and why did you write the book?

James: The book, the title of the book is obviously a minor play on Donald Trump’s demand for my personal loyalty, but what it really is a reference to is my belief that the best leaders I have worked for, were people who made decisions by lifting their eyes above the urgent, and the angry, and the immediate, and asked instead what really matters here in the long run. What are the values this institution? How will this be seen years from now? What are the higher values and points of orientation that should guide this decision? When it’s so easy to make decisions by staring at the lower level, pain and anger, you don’t want to be embarrassed, you’re worried about the quarterly numbers, it’s going to be a bad story. That the best, I believe, lift their eyes and are loyal to the things above that, not tribe, not personal bank account or personal reputation, but the things that matter in the long run, and so the book is about, story driven about how you lead with an eye towards those things, and I wrote it because I worry today that especially young people have a cynical view of leadership. That it seems so crappy, not just in the government but in the non-profit, in sports, in entertainment.

James: There’s so much awfulness that I worry that they wouldn’t see how often it’s done well and what it looks like when it’s done well, and I could illustrate that through people I had worked for, mistakes I had made, things I had done well, and tell that story. I hope to inspire them and to give them a roadmap for how to do it, especially when it matters most.

Chitra: How did A Higher Loyalty come into play in some of the major standoffs you and justice department had with the Bush White House, particularly of warrantless surveillance and inhumane interrogation techniques by US intelligence agencies after the 9/11 attacks?

James: I think those collisions are really important examples of what I mean by A Higher Loyalty. We were in situations where the leaders of the executive branch, especially the vice president, then Dick Cheney, in good faith believed that these things, this surveillance, this torture, was essential to the security of the United States, and we on the other side of Pennsylvania Avenue said actually, take the surveillance program, this violates the law. And so we at the Department of Justice cannot sign off on this, and he looked me in the eyes, as close as you and I are today and said, “Thousands of people are going to die because of what you’re doing.” Talk about a temptation to keep my eyes down there in the urgent and the angry, and what helped me and the lawyers around me is we tried to lift our eyes and ask ourselves, so what is important about the department of justice in the long run and how will this be viewed three years from now, five years from now. No one is going to look at me and say, “Oh, you approved something you thought was unlawful and you did it because the vie president was angry at you? Is that what the answer is?”

James: It’s an example of a group of people looking above that urgent, to try and be guided by the things above in both the surveillance and in the interrogation context and doing something else which is floating out of the room. Part of the higher loyalty idea is look up above that urgent and angry and drift out of the room, and look back on this moment from the future and look on this moment from other places and see how it might be seen through the eyes of others. That’s the essence of judgment and that helps you see that there are things that should be steering you far about the anger that’s in the room you’re sitting in.

Chitra: So this idea of higher loyalty I think probably got you in a ton of hot water after you became appointed as the FBI Director by Barack Obama in September of 2013, and as most people know, you’ve been excoriated by both Republicans and Democrats for your handling of the bureau’s investigation into the Hillary Rodham Clinton email controversy in the lead up to the 2016 elections, and in fact many in the US believe that you are responsible for handing the presidency to Donald Trump because of numerous public statements you made to the press and to congress about the status of the investigation, even as Americans who are making up their minds about whom to vote for. How do you even today deal with the weight of those accusations that you handed Donald Trump the presidency?

James: Well, at the most personal level I hope not. All that does is increase the pain. It doesn’t change how I think about the decisions, I secretly hope, and now it’s not a secret anymore. I secretly hope that someone proves some day that what I did, what we did, was irrelevant. But honestly, and I hope people take this the right way, it doesn’t change how I think about the decisions. I anticipated in making those decisions that there would be brutal criticism. We anticipated, one of my best lawyers asked me a question. “Should you consider that what you’re about to do may help elect Donald Trump president?” And I thanked her for the question and said, “No, I can’t. I have to ask what’s the right thing to do here.” I lead an institution of justice, what is the right thing to do? I got to lift my eyes above the political, and so we did, and I, reasonable people are going to see this differently.

James: We were dealing with situations I don’t think anyone’s ever encountered before, so I’d be a fool to say I’m certain I was right, but I do think we were right and made the least bad judgment throughout that awful case, and so I’m of two minds. I’m proud of the way we made the decisions. I think the decisions we made will stand the test of time, that reasonable people when they understand them will say, “Oh, that was a lot harder than I thought.” And I hope that it proves, someone proves we had nothing to do with the outcome because that would reduce the pain. That’s how I think about it.

Chitra: And in tandem with them Hillary Clinton email investigation at the time, you and the bureau and the justice department were also dealing with and grappling with the enormity of the Russian interference in the US elections, which they were doing at multiple levels, and this investigation was causing massive pain to the president and to the White House. You have described in the book in great detail how the president tried to win your loyalty by attempting to get you to shut down the investigation. Tell us a little bit about what that process was. How often he tried to do that and in what manner?

James: My encounters with President Trump from January of 2017 through my getting fired in May, at least in my perception, it was a series of efforts by him to pull me close and me to push away. Him to pull me close to make me part of his team, it began even before he was president when I met him on January the 6th, praising me then at dinner explicitly asking for my loyalty. Having encounters with me with just the two of us, which is very, very unusual for an FBI director to be alone with the President of the United States, and that may strike people as strange, but the reason it’s so unusual is since Watergate, presidents, and congress, and the FBI, and lots of other constituencies have tried to keep a distance between the two, because one of the lessons of Watergate is there’s nothing but trouble if the power that resides in the FBI director is too close to the power in the presidency, and so you work for the president because you’re in the executive branch, but you have to be spiritually, culturally apart because you may need to investigate the president, as it turned out here. And so I perceived him to be trying to pull me through that norm and I would push away. He would pull me, I would push away.

James: The most striking moment was at our dinner together. First, the most striking thing initially was that we were alone. I thought it would be a group dinner, and then he looked at me across his salad and said, “I need loyalty. I expect loyalty.” I was so stunned in that moment and realized right then two things. First, this president either doesn’t know or more likely doesn’t care about that norm of separation, and second, this president doesn’t know anything about leadership, because a leader never asks for loyalty. A leader never asks for anything except high performance. A leader generates an environment of love by the way in which she conducts herself, but the last thing you do as a leader is say, “I want you all to be loyal to me.” That you have to ask is an indication that you’re not an effective leader.

Chitra: You draw some striking parallels between the president’s actions and some of your early experiences with the mafia. What were the parallels you saw and see?

James: Yeah, I kept, this popped in my head actually that the very first meeting with the president-elect to brief him on the Russian interference with his team, and this image a La Cosa Nostra boss meeting with his team popped in my head. I pushed it away because it seemed too dramatic, but it popped back again, and it kept coming back to me, and back to me, and back to me over my encounters with the president and here is the reason. It’s not that I believe Donald Trump is out breaking legs or hijacking trucks, it’s that he has a leadership culture that reminds me of a Cosa Nostra boss, where the entire thing in centered on me, the boss, and all that matters is what you will do for me. What’s your obedience, what’s your loyalty, what are you bringing to me. It’s not about any higher values. There are no external reference points. It’s not about history, or tradition, or philosophy, or law. It’s about what are you going to do for me. That boss centric leadership, which is at the heart of Cosa Nostra, very similar to the way Donald Trump operates, and I think more and more people have seen this. I don’t think I was nuts to see this early on, but the cultures are very similar.

Chitra: After his repeated attempts to pull you into his circle had failed, you found out in, I guess was it May of 2017 when you were at an FBI field office in Los Angeles that you had been summarily and very publicly fired by watching it on the news. You didn’t know it until then. Were you surprise that it actually happened, and what were your thoughts?

James: I was stunned, and I know that may seem strange to folks, but I didn’t expect to get fired. I thought by, after five months I knew the president didn’t like me, but I thought that was a good thing because meant there was going to be a cold front that settled, that kept us apart, which is what the American people have wanted since Watergate as I said, and also I’m overseeing the Russia investigation, and so it never entered my mind that I might be fired, and so I was standing there talking to a group of employees in a large space in the LA field office and on the back wall were televisions, and from looking at the televisions in the background while I’m talking to the employees about the mission of the FBI and why it’s so important that I learned that I’ve been fired, it left me a bit numb honestly because well, to find out that way. I traveled, this won’t surprise your listeners, I traveled with communications gear. Anyone up the chain of command could speak to me any time of the day, secure or non secure within seconds, and nobody called. I found out about it from the press.

Chitra: After you had been fired, you decided not to remain quiet and you took steps to ensure that the Russia investigation would continue, what did you do?

James: As I said, I was numb, so I was kind of moping around my house with a mob of press people at the end of my driveway and I was hiding from them, and I, the president tweeted at me. I was fired on a Tuesday, so about three days later the president tweeted at me that I’d better hope there aren’t tapes of our conversations before I start leaking to the press. Now, I hadn’t been leaking to the press, I hadn’t had any contact with the press. Two nights later, three nights later I woke up in the middle of the night and it dawned at me while I was asleep the significance of that tweet, which hadn’t occurred to me. Shows you how numb I was. I should’ve seen this right away.

James: Wake up in the middle of the night and all of a sudden I’m like, “Oh my god, tapes. There could be tapes of our conversations where he’s telling me to drop a criminal investigation.” It’s not going to be my word against his word, there may be a tape of that. Someone has to go get the tapes. And I figured the FBI, who I wasn’t in touch with, that they had seen that, but I didn’t trust the leadership of the Department of Justice, the then attorney general and deputy attorney general to go get those tapes because it would be an aggressive investigative move, and so I thought, “Someone has to get the tapes. A special prosecutor has to be appointed.” And the deputy attorney general had promised to consider that, and I thought I can force that, or at least help force that if I make clear to the public that there’s something that there might be a tape of that’s really important. And so I asked a friend of mine who is also one of my lawyers, but I didn’t ask him to do this as a lawyer, I asked him to get out to the media, the substance of my conversation with Donald Trump on Valentine’s Day of 2017 to make clear that there is something that investigators are going to want to find and see, so someone go get the tapes.

James: Now, the president has since said … So I did that, and then when I was asked about it in my testimony of course I told the truth about it, and I don’t know to this day whether there are tapes. The president has said there aren’t tapes, but the president is a chronic liar. Even if you support him you know that’s a true statement, and so I don’t know whether there are tapes of our conversations, but I thought I am a private citizen, private citizen can talk about conversations with the president that are unclassified, this was unclassified, and so I could do it. I probably should’ve done it myself, but that would’ve been at the end of my driveway to a mob. I thought, how will I ever stop that process? So I asked one of my friends to do it.

Chitra: And eventually of course the special prosecutor was appointed and he has now issued his report. What do you think of the report?

James: The report is a really important public service. Very few people in congress know that because they haven’t read it, which is shameful. It is in two respects really important. It collects in vivid detail the overwhelming case that the Russians came for our election to damage our democracy, to hurt Hillary Clinton, to help Donald Trump. No fuzz on that, and if you read that report you walk away knowing why we had a high confidence view of that. Second, it collects the evidence that the president may have obstructed justice repeatedly, which is very, very important. And so I think those two things are great public services. The way the special council structured the report has led to confusion and also left it open to be distorted and frankly lied about by the president and the attorney general, and I think they’ve taken that opportunity, which is a shame.

Chitra: Can then your lifelong hatred for liars, and bullies, and your characterizations of President Trump as engaging in both, there seems a certain dark irony that you’ve been accused of putting Trump in power. How do you cope with that?

James: I think the way I said earlier is I … If there was something I would do in hindsight significantly differently, I would feel worse honestly, but I don’t feel that way. I’ve thought about the decisions I made a lot, and I ran the margins of the things I would do differently, but in substance I would do the same thing on the same facts. So I don’t feel responsible for him being in office. Now, full stop, I think he’s a deeply amoral leader and a threat to many, many important traditions and norms of the United States government, and I think one of these parts of my weird life that’s really important nowadays, I have to speak about that and I never imagined this part of my life, but if I don’t speak who’s going to? About just what the FBI is like, the Department of Justice, the importance of the rule of law, the importance of having a president who is not a chronic liar. So that has put me in a place that I don’t love being in that role, but I’d be a coward to avoid the role. I’m eager for it to go away next November.

Chitra: You’re going to continue to speak out against Donald Trump until then?

James: I am, and never talk about policy. I don’t think anyone’s ever heard me offer a view about taxes, or immigration, or guns, or abortion. Those are really important things, but above those things are a set of values that are the glue that holds this country together, and Donald Trump is a profound threat to those values, and it’s thoroughly depressing that Republicans either can’t see it or refuse to act on what they see, but I think it’s the obligation of everybody who sees it and cares about those values, without regard of what your policy preferences are, to speak about it and to act on it, and so I’m going to do that.

Chitra: One last question. What is your life like these days? I mean, you are such a recognizable figure, and you’ve been a very polarizing controversial figure. Can you go out in public and, do people come up to you? Are they angry, do they applaud? What’s it like to be Jim Comey these days?

James: It’s weird. It was never one of my career goals to be an unemployed celebrity, I’ve achieved that, and it reminds me of why I would never want to run for office or be someone where fame was at the center of your existence because it’s both weird and it’s a little bit like cotton candy, it’s empty calories. It’s an endless pursuit if you really want to be famous, so mine will go away which is the good news. In the short term nearly everyone is nice. People come up to me all over the country and all over the world literally, and are very, very supportive. Now, there’s a selection bias there because I’m sure haters stayed at a distance. They’re probably afraid I’m carrying a gun or something. I’ve only had two times I think in the hundreds and hundreds of encounters where someone has said something unpleasant. More often people whisper things of, statement of gratitude that I’m out there speaking. But yeah, I’m a giraffe, so it’s really hard to hide. I was in Amsterdam walking on the street and a truck screeched to a stop and a West African immigrant driver shouted my name. Jumped out of the truck blocking traffic, said he had to have a picture, explain where he’s from, I think he’s from Ghana, and we took a picture together. I turned to my wife and I said, “This is bizarre, but it will fade.”

Chitra: It’s been a great conversation, Jim. Do you have any closing thoughts?

James: No, I think it is, there … Maybe one. There is no better time to think about leadership than now, and I’m not going to argue that Donald Trump has been good for us, but he has forced conversations around dinner tables all over this country about truth, integrity, and what leaders really should be like, and I think, remember I said I was afraid young people will be turned off, I think the reverse has happened. Young people are inspired and engaged, and so those of us who have seen good leadership, struggle with leadership have the perfect time now to talk about it because Donald Trump has put it in the center of the table, so thanks for this chance.

Chitra: And thank you so much for joining me.

James: Thanks.

Chitra: Jim Comey is the former director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. His book is called A Higher Loyalty, and can be found on Amazon and local bookstores.

Chitra: Thank you for listening to When it Mattered. Don’t forget to subscribe on Apple Podcast or your preferred podcast platform, and if you like the show, please leave a review and rate it five starts. For more information including complete transcripts, please visit our website at goodstory.io. You can also email us at podcast@goodstory.io for questions, comments, and suggestions for future guests. When it Mattered is produced by Jeremy Corr, CEO and founder of Executive Podcasting Solutions. Come back next week for another episode of When it Mattered. I’ll see you then.