Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Email | RSS

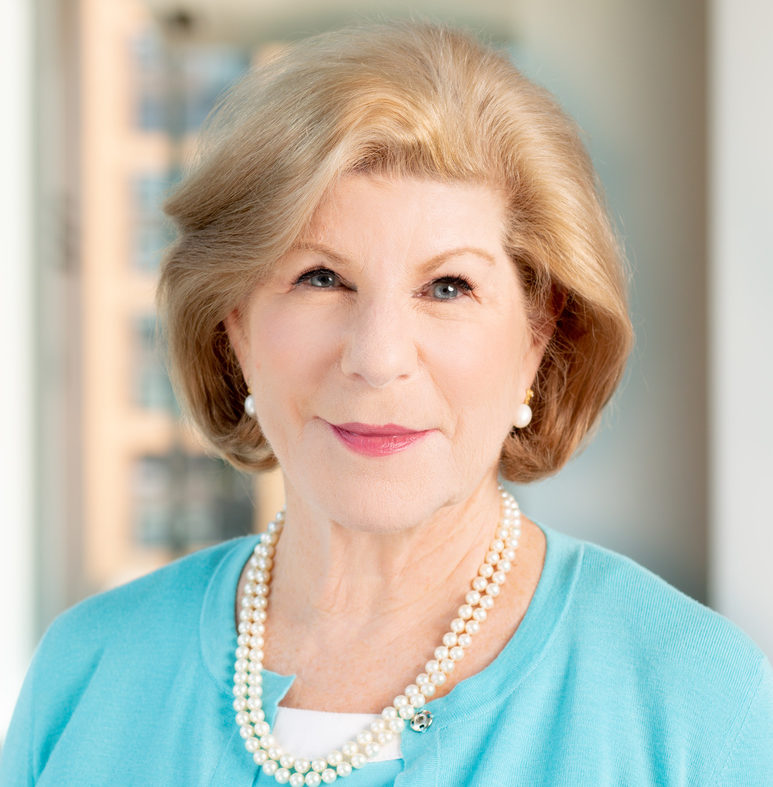

Ep. 8 — An award-winning reporter struggles with balancing a demanding job and managing a family crisis and learns the true meaning of duty and family / Nina Totenberg, Legal Affairs Correspondent, National Public Radio (NPR)

In this episode, NPR’s Nina Totenberg confesses that her youthful admiration for teen fictional detective Nancy Drew played a formative role in pursuing journalism as a career in an era when female reporters were a rarity. Totenberg reveals how she broke free from the confines of fashion and wedding news reporting via press releases and became one of the most acclaimed and celebrated legal reporters in the country. And she compares the challenges she and other working women of her generation faced to how women are handling sexual harassment today in light of the #MeToo movement.

Totenberg describes what it’s like to have covered the U.S. Supreme Court for decades, and she reads the tea leaves on where this increasingly conservative court may be heading in the coming months. And she walks us through her difficult days holding down a high-profile job and taking care of her late first husband, Senator Floyd Haskell (D-Colorado), after he suffered a serious head injury from a fall and battled for his life for months in an intensive care unit.

Totenberg shares with us the advice that Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg gave her to help her through those trying times. And she talks about her own survival from a snorkeling accident when she was hit by a power boat during her honeymoon with her second husband, who just happened to be a trauma surgeon. Through these crises, Totenberg reveals how she came to have a renewed appreciation for friends and family and the importance of duty in life’s journey.

Last but not least, Totenberg ends the conversation with a heartwarming anecdote about her virtuoso violinist father Roman Totenberg’s stolen Stradivarius.

Transcript

Chitra Ragavan: Hello, and welcome to When It Mattered. I’m Chitra Ragavan. On this episode, we will be talking to Nina Totenberg, National Public Radio’s award-winning legal affairs correspondent. Totenberg’s coverage of the Supreme Court and legal affairs have won her widespread recognition and acclaim and earned many awards. She’s often featured in Supreme Court documentaries, most recently in RBG. As Newsweek put it, quote, “The mainstays of NPR are Morning Edition and All Things Considered. But the créme del la créme is Nina Totenberg.” Nina, welcome to the podcast.

Nina Totenberg: It’s my pleasure, Chitra.

Chitra Ragavan: What was your path to becoming a reporter?

Nina Totenberg: Well, when I was a girl, really a girl girl, I was a great fan of Nancy Drew, and Nancy could do everything. And, of course, she had no mother. Her mother was dead, so she didn’t even have to compete for her father’s affections. And she had a boyfriend, Ned, and a roadster, and she solved all kinds of mysteries and could do a jackknife dive. And I wanted to be Nancy Drew, and I thought the mystery part was something that I could do. And so I think that that made me, at first, interested in journalism.

Nina Totenberg: And then later, when I was teenager, I read Theodore White’s, The Making of a President, 1960, and I thought, “That’s really what I want to do. I want to be … ” The elegant way of saying it is, “A witness to history.” The inelegant way of saying it is, “I want to be a gossip,” in the most regal sense. I mean, my colleague, Cokie Roberts, often says that, “Historians get it wrong. They make it boring.” But history is gossip. It’s what’s going on and the story behind the story as well as the story in front of the story. And that’s what I wanted to do from the age of about 16 on.

Chitra Ragavan: So how did you go from being a fan of Nancy Drew to actually becoming a real reporter?

Nina Totenberg: Well, it was very difficult when I started out because people just told you they didn’t hire women or, “We don’t hire women for the night shift,” which was a classic way to get a first job. It’s true. The Civil Rights Act was in place, but it was pretty young then, and most employers really didn’t think that they had to abide by it for women. So it was very hard to get the first job.

Nina Totenberg: My first job was on the women’s page at then the Record-American in Boston, now known as the Herald-American, and it’s now a Murdoch paper. It was a Hearst paper then, and it was unbelievably boring. I mean, I just wrote fashion but not like we read in the newspapers today. It was sort of rewrites of press releases. I wrote stories about weddings, but they were just rewrites of what people sent in about the seeded pearl gowns and things like that.

Nina Totenberg: And so I would go out at night to cover other stories with other reporters. I was their, “Leg-man,” as it were, and they could leave the story to go back to file, and I would call in with new details about the fight at the school committee or the latest, or I went around with a photographer all night long for most of the night. We would have a police, fire, and state trooper radio in the car, and we would just go where the action was. And I would phone those in to go with a short story to go with the photograph. And that’s how I got my first job.

Nina Totenberg: And then I went to work for the Peabody Times in Peabody, Massachusetts. It was a paper that published twice a week and was part of a chain in that area of Massachusetts, and I covered everything. And there was even a day, I think, after the election where every byline on the front page was mine.

Chitra Ragavan: I bet you loved that.

Nina Totenberg: But it was great experience. I covered everything from the cops, to the school committee, to the elections, to features, to the day that we heard that there had been a robbery at a local bank. And I called up the bank and I said, “Hi, this is Nina Totenberg from the Peabody Times. We understand there’s been a bank robbery.” And the guy says, “This is one of the robbers.” They were so hopeless that they ran away with a stream of cash, and that’s how the cops were able to arrest them. And I was able to write a hilarious front-page piece about it.

Chitra Ragavan: That’s a wonderful story. What was it like to be the only woman or one of the only women in the newsroom in those days?

Nina Totenberg: It was, I suppose, challenging, but I was so grateful to have a job. I usually was the only woman in the newsroom, or when I was doing all those things that were not on the women’s page, there was one woman who was a crime reporter, Jean … I can’t remember her last name right now. And I would look at her longingly, and she was a really tough broad. And I learned to be a young, tough broad if I wanted to get ahead.

Chitra Ragavan: And how did others respond to you, like the guys in the newsroom and the printers and all of them?

Nina Totenberg: Well, when I went to work for the National Observer, which was the newspaper that was owned by Dow Jones, and Dow Jones then owned the Wall Street Journal, and they wanted to have a general circulation weekly newspaper. And it was a really formative experience working for the Observer because I covered all kinds of things, and I had very good people who were my editors and who made me understand how to do this job so, so much better.

Nina Totenberg: And the difficulty was, I was the only woman on the news desk, and the guys would go to lunch and not take me with them. And part of my job was at the end of the week, I was the sort of supervisor for the printers. So when I used to walk down what seemed to me like a very long hall from the newsroom down to where the little cafeteria was, which was all Coin-O-Matic machines, but where you could sit and have your lunch, they would line up sometimes along that wall and just sort of dissect my body as I walked down.

Nina Totenberg: Now I have to tell you, I liked these guys when I was working with them, and they were very nice to me. They used to tease me, and they would have some jokes that would not be acceptable today, and I just sort of ignored them and went on. But it was very difficult. And when I would go down and cover the Congress and I would call some Congressman off the floor and he would come off the floor, very often they did not look me in the face. They looked considerably lower, and I just learned to roll with the punches. I was just glad to have a job.

Chitra Ragavan: It would be different in today’s era, right?

Nina Totenberg: Oh, it’s night and day. I mean, now men are really afraid, and they should be. But in those days, they had no frame of reference. They had no governors on this kind of behavior, and nor did, occasionally, bosses who today would be fired for what they did. But I did not see that there was any recourse. Occasionally in that era, there would be a woman who would sue and even win, but it was a career-ender, and I didn’t want to do that.

Chitra Ragavan: Working with the printers, you also say you developed a very special skill, a technical skill. What was that?

Nina Totenberg: Oh yeah. I could read upside down and backwards because you were looking in those days at hot type and they would say … I’d look and I’d have to say, “Okay, we need to cut an inch here.” And I’d say, “Why don’t you do it at the paragraph that ends … ” and I would read what it said. I don’t think I could do that anymore, nor is probably my eyesight good enough to do it with somebody’s documents on their desk. But I wish I could because it’s a great investigative reporter’s skill to be able to read upside down and backwards.

Chitra Ragavan: How did you start covering the Supreme Court at NPR? I mean, you had come a long way by the time you came to NPR from being that reporter who was writing about women’s issues and cooking and fashion to covering one of the most difficult beats, which is the Supreme Court.

Nina Totenberg: Well, when I was at the National Observer, they did assign me to cover the Court and many other things, but the Court, I was supposed to write about the Court, and I was good at it. I won a bunch of awards. And when NPR hired me, it was a very small place, and they were looking for a legal affairs correspondent, somebody who knew the Court and knew other things as well. And they hired me to do that, and I covered everything. My beat was the Supreme Court, the judiciary committees of the House and Senate, the justice department, every scandal, every special prosecutor, and oh, yes, the intelligence community.

Nina Totenberg: Now fortunately, in the beginning we only had one program, All Things Considered, so I wasn’t filing for many programs a day. Even our newscast unit was not round the clock, and there was no digital. And today, no human being could do that no matter how hard she worked because we have so many platforms to file for that there’s a limit to what one human being can do, even if she’s pretty fast.

Chitra Ragavan: What’s it like covering the Supreme Court compared to other beats where you are building a lot of sources, you can take people out to lunch? It seems like with the Court, it’s a very different ballgame.

Nina Totenberg: Yeah. You develop sources and take people out to lunch, but they’re lawyers and professors and people who know about specific issues and sometimes people who have clerked on the Court, if you’re doing that kind of a story about how the Court works. But the justices, I know most of the justices, but mainly I know them from before when they were justices.

Nina Totenberg: So Justice Ginsburg, who, as we do this, I did a big interview of her about a week ago, and it made a lot of news. But I’ve known her for over 50 years when we were both very young women. She was in her 30s. I was in my 20s. And I’ve known her through all of that period of time. She was a lawyer, an advocate in the Court for women’s rights. And the very first time I met her was on the phone. I was reading a brief. It turned out to be the first brief arguing that women were covered by the 14th Amendment guarantee of equal protection in employment.

Nina Totenberg: And I didn’t understand that because I thought the 14th Amendment was essentially for freed slaves because that’s what it traces back to. And I flipped to the front of the brief, and it was written by a law professor at Rutgers named Ruth Bader Ginsburg. And I called her up, and I got an hour-long lecture, essentially. And from then on, I would call her about her cases, other cases, and I would call her to see what she was doing that was interesting that I should keep tabs on, that kind of thing, and we became friends.

Chitra Ragavan: It must be interesting for you to see her get this new cult status as a pop culture icon and even for the younger generation, especially with the documentary.

Nina Totenberg: It’s amazing. I remember when she couldn’t get a job as a federal district judge in New York. She applied. She was interviewed. They said, “You don’t know anything about securities law,” and she didn’t get … she wasn’t recommended. And I remember her saying to me, she telling me that she said to them, “Well, how many of you know anything about sex discrimination law?”

Chitra Ragavan: She was a tough cookie.

Nina Totenberg: She was a tough cookie, even then.

Chitra Ragavan: You won a lot of awards and earned national recognition when you broke and covered stories related to the sexual harassment allegations leveled by a University of Oklahoma professor, Anita Hill, against Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas. Looking back on that story and looking at today’s Me Too Era, you were early in terms of the coverage of those kinds of issues. Do you have any thoughts, just looking back at coverage of the Anita Hill controversy and how it was covered then and now?

Nina Totenberg: Well, I suppose that’ll be in any obituary written about me, that I broke that story, and I do think it was a very important story just as I think everything that’s happened in the Me Too Movement is very important to come out, some of which I didn’t know, all of the Epstein, Weinstein, all that stuff, and about some of the people in our profession who were people I knew pretty well and I considered at least casual friends. And I had no idea that they were doing what they were doing.

Nina Totenberg: But there is a generational divide between people like me who were just glad to get the job and tolerated things that should not be tolerated and would not be tolerated today, and young people who have basically an execution-at-dawn mentality. There’s no tolerance, and there’s often not a lot of subtlety between what is unacceptable but reprimandable behavior and curable and the kind of thing you simply can’t tolerate, you fire somebody for.

Nina Totenberg: And I think older women like me are more tolerant in that regard. And I’m not saying that they’re wrong. There is a very discernible difference between the older generation of women who have been at work for at least 40 years and younger people who have been at work often for less than 10. And I worry, I think we worry in the older generation, that if you get too militant, men will be unwilling to mentor you. And although they’ll never say it, they will not promote you as consistently, and I worry about that.

Chitra Ragavan: You’ve been covering all of these huge national stories. I think what a lot of people don’t know is even as you were covering a lot of those big stories, you went through a time in your life when you were dealing with tremendous adversity, and that was dealing with your personal crisis of the deteriorating health of your late husband, the Senator Floyd Haskell of Colorado, to whom you were married almost 20 years. I remember those days. Tell us a little bit about what it was like to manage a very difficult demanding beat and caring for your husband.

Nina Totenberg: Well, I found out I was stronger than I thought, but I also found out that all of my friends and family were just beyond essential for my ability to cope and my mental health. On one occasion, I was away covering the Oklahoma City Bombing, and my husband, who was in the ICU, crashed. And they thought he was going to die, and I was racing back. And Cokie Roberts, my friend and colleague, showed up. She heard about it because she heard about it, and she just went tearing over to the hospital to be there so that Floyd could see somebody who was not a doctor or a nurse looking at him.

Nina Totenberg: And when I went careening into the ICU and he recovered, I mean, he rallied, I really thought, “I don’t know if he would have held on the way he held on as long as he did if Cokie weren’t there,” or my sisters were, particularly in the beginning after he had this terrible fall and head injury, they would come every weekend, and they would do all kinds of wonderful things for me. My sister, Amy, who’s now a judge, had a former intern who had worked for her, and she was in Washington. And she grabbed her and she said, “You have to go buy her a small TV for her bedroom, and sign her up for cable and then install it. She won’t know how to do that, but she needs diversion. She can’t have moments where she’s just thinking about what’s going on.”

Nina Totenberg: And I got wonderful advice from … My mother said, “Nina, your brain needs a rest,” at one point. And she said, “You need to get some antidepressants.” And I thought she was crazy, but I called somebody that I knew who was a psychiatrist who said, “A lot of people we prescribe antidepressants for don’t really have problems. They’re just depressed. You have real problems at the moment. You have to take care of this man, make sure everything goes right, and do your job. Let’s try it.”

Nina Totenberg: And it worked. It didn’t make me happy, but it made me better able to cope and to stop crying in my cubicle, which is what you undoubtedly remember. And then Ruth Ginsburg gave me wonderful advice. She said, “You have to stop hanging around the hospital all day. Go back to work. He’s going to come home eventually, and you’re going to need to be able to take care of him. The work may not be the best work you’ve ever done, but it’ll be perfectly good work. And you will not be sucked into the maw of the hospital routine, and you will be better able to take care of him when he comes home.” And that turned out to be exactly right.

Chitra Ragavan: Well, those days also, at least I was there to see it, showed your incredible discipline and work ethic. You would go to the Court. You would come back. You would file your stories. You would see him in the hospital, and in-between, I remember you crying in your cubicle. And I remember NPR had built a little privacy partition for you so you could-

Nina Totenberg: Cry in private.

Chitra Ragavan: … cry in private. And there was a lot of crying, but you never missed a deadline. And I think for a lot of young people today, that kind of work ethic is something to be talked about and reminded of, that that’s what you need to be like in the workplace.

Nina Totenberg: Yeah, well, it is best for your own mental health to do that. If you have pride in your work … I remember somebody calling me up, some conservative activist calling me up and saying, “Why aren’t you covering Paula Jones the way you covered Anita Hill?” And I said, “Because I have a husband in the hospital at death’s door in the ICU for months, and I don’t have time to add one more thing to my plate.” And that was true. That was absolutely true.

Chitra Ragavan: So after a long illness and being in and out of the hospital, your husband passed away. And you subsequently met another wonderful man, a trauma surgeon, and you ended up on your honeymoon requiring a trauma surgeon.

Nina Totenberg: Well, I’ve been lucky enough to be married to two very sweet, wonderful men. And on our honeymoon, I got run over by a little power boat. Thank God it was little, and there I was quite far out from shore, we were snorkeling, and had my head sliced open and, as I later found out, also the propeller hit the … had like 20-inch or 15-inch gashes right up my body, but I didn’t know that at the time. I didn’t even realize I’d been hit, but when I started to go into shock, my husband just levitated out of the water about and got this boat that was hauling some children around to come get us. We’d started to swim, and he was trying to haul me in. This is very difficult when somebody is bleeding, and thank God we never thought about sharks, neither one of us.

Nina Totenberg: And fortunately for me, everything turned out all right and I was fine. But I did recuse myself when there was a case about a similar boating accident that got to the Supreme Court. It was a tort case, and I went to my boss. I said, “I don’t think I can be unbiased in doing a setup about this case. I can probably do a perfectly serviceable job when it’s decided because I’ll just say what the Court said, what the facts were and what the Court said. But I don’t think I ought to be going to hear this case argued and na, na, na, na, na.

Chitra Ragavan: That was a life-threatening moment for you. Did you change in any way after that?

Nina Totenberg: Really, no. Again, the family rallied. My husband at the time was chairman of surgery at one of the partners hospitals in the Boston area, and we went back to Boston and he had me checked out there. He said, “You need to go back to work.” Now we were in the middle of the Bush versus Gore, and I just did have to go back to work.

Nina Totenberg: And my brother-in-law came to Washington and drove me around and cooked meals for me, just for a few days, just so that I had somebody, I wasn’t living alone when I was still pretty beat up. And there was a famous moment on the steps of the Court where Matt Lauer asked me live, after talking about what was going on inside the Court that day, he said, “Nina, let me just stop here for a minute. We’ve heard you had a terrible accident on your honeymoon, and you look just fine.” And I said, “Matt, it’s a triumph of drugs and makeup.”

Chitra Ragavan: That you were able to keep your spirits up even at that moment I think is pretty remarkable.

Nina Totenberg: Well, if you don’t keep a sense of humor, you can’t survive.

Chitra Ragavan: You wanted to be a witness to history, and you have been a witness to history over these past few decades watching the Court grow and change in many ways. Looking at where we are now with the Court, what do you see? What’s the direction? Can you make any predictions at all in terms of where we are going once the Court convenes?

Nina Totenberg: Well, we know the direction. There are now five solidly conservative justices, and that’s a majority. And they are not just solidly conservative. They’re more conservative than any Court majority in memory, perhaps back to the, in some ways, potentially back to the 1930s. And I don’t know how conservative this Court will be. I think that’s yet to be determined.

Nina Totenberg: And there’s always the possibility of another vacancy during this administration. And Mitch McConnell has said he would push through a Trump nominee, even though that is contrary to what he did for President Obama when there was an unexpected vacancy then. We could have a six-to-three majority, and then no single conservative justice would be the so-called swing justice. You’d need two. I don’t know how far this is going to go and how conservative this Court is going to be, but I do know that it could become a real flash point in elections in the coming years.

Chitra Ragavan: And what does it mean for women’s reproductive rights?

Nina Totenberg: I think probably they are in danger in some states, that the Court is … I’ve always thought the Court would whittle away at Roe versus Wade but leave intact the basic right to have an abortion. I’m not even quite sure of that now, having talked to a lot of people about this. And that might extend as well to birth control and the availability of birth control. Beyond that, I do think that women’s rights are pretty well-established and unlikely to revert to times when women were not vigilantly protected by the law. So I do think there’s a line to be drawn there.

Chitra Ragavan: The late Justice John Paul Stevens recently passed away, retired justice, and it opened up a lot of conversation and debate about the nature of the Court and where it’s headed and what he represented as a moderate Republican who then became kind of the hero of the left. What are your thoughts on his legacy and how that reflects on where we are today?

Nina Totenberg: Well, he always was a judge’s judge, and that’s really why he was picked because he had no real partisan background, although he’d been a lifelong Republican. And he was seen as sort of a moderate conservative, and I think he’s right, although he changed a little bit on a couple of things like death penalty questions. I think that he didn’t change so much as that the Court changed around him and became so much more conservative that he, who was in the center when he was named to the Court in the mid-’70s, by the end was the most liberal member of the Court.

Nina Totenberg: I don’t think that we are going to have huge surprises from the people who are appointed to the Court in the future. Democrats have, by and large, named very establishment moderate liberals, but they are liberals. Make no mistake about that. They like the rules that have been laid down, up until now. The newer members of the Court definitely want to change those rules. They want to have, in every area I think almost, a Court that’s much more accommodating, for example, of religion in the public sphere, that’s much more accommodating to the state’s ability to curtail reproductive rights, and I could go on and on, and is much more friendly to the idea of curtailing the federal government’s ability to regulate all those sorts of things. Gun rights, essentially same thing. So you’re going to see a Court that is far more conservative. This new five-to-four majority hasn’t really started to take off yet.

Chitra Ragavan: Looking back on your career as a reporter and also some of the adversity you faced with your dealing with your first husband’s illness and the boating accident, are there any lessons that you’d like to share with our listeners?

Nina Totenberg: I always tell kids when I do a high school graduation and even sometimes a college graduation, “I think that doing your duty will serve you well, and that often is very difficult.” If it’s your husband who’s sick, it means you do your duty by him. You make sure that he’s cared for. You take care of him. You are always there for him if he needs you. You’re very vigilant about his care.

Nina Totenberg: But so many people did their duty for me as well. My friends, who gave up lots of their time to help me, my family, who did the same thing. Cokie Roberts and Linda Wertheimer brought dinner to my house for months, I would say once a week, and we would have the equivalent of a dinner party with Floyd, my husband, and it cheered him up and it cheered me up, and I didn’t have to cook. They brought the dinner.

Nina Totenberg: You don’t think that’s easy, do you, just to do that? Or Cokie would occasionally call, or Linda, and they’d say, one of them would say, “I’m away for two weeks, but if you need me, call, and I will find somebody who can help.” That’s an amazing thing.

Chitra Ragavan: You’ve shared some of the sadder anecdotes with us and the difficult moments in your life. But there’s another anecdote, a happier one, that has to do with your father, the famous violinist, Roman Totenberg. Tell us that story.

Nina Totenberg: Well, my father was a great virtuoso violinist and teacher in his later years. He died at 101, teaching still on his deathbed. And in 1980, I think it was, he gave a concert in Boston and went out one entrance of the room to greet people, and somebody came in the other entrance of the room and stole his violin. It was a Stradivarius, worth an enormous amount of money today, considered very valuable then but nothing like today. And the FBI was immediately called in, and it was never recovered.

Nina Totenberg: And 35 years later, I’m sitting at my desk. And my husband calls and says, “The FBI’s trying to reach you.” And I had just filed. He knew not to call me on deadline. He knows not to do that. So this was like after 6:00. It was the last day of the Court term. And the next morning, I called the FBI at the number they’d left, and it was Agent Chris McKeogh. And he said, “Well, Ms. Totenberg. We think we’ve recovered your father’s violin.” And I sort of thought, “Yeah, right.” And I said, “Are you sure?” He said, “Yeah, we’ve had it appraised already. We’ve had it looked at.” And he said, “But we don’t want you to tell anybody because we need to check things out.”

Nina Totenberg: I said, “Well, I have to tell my sisters.” So I called my sister, I called my sister Amy first, and I knew she’d be running early in the morning. She’s a federal judge in Atlanta. And I said to her husband, I said, “Tell her to call me the minute she gets in, but it’s not bad news.” And then we got my sister Jill on the line and I told them this. We started laughing and crying. It was a humongous story because it was a good news story. And I, of course, insisted on breaking it once we got it returned to us. It was all done. I got a lawyer to represent us. We paid off the insurance company, and it was turned over to us in a humongous press conference in New York, in the Southern District of New York, with Preet Bharara presiding over this.

Nina Totenberg: And the three of us spoke. There were, I think, 25 camera crews there and I don’t know how many reporters and photographers. It was wild. They told me it was the biggest press conference than even the mob press conferences when they indict some huge family, mob family. So it was on the front page of the New York Times. It was on the front of the style section, a huge story. It was in every newspaper, on every TV thing in the country. And my brother-in-law sent me a compilation of the little clips that he found online from television of me talking in many different languages because they would dub in me in Japanese or French or German or Russian talking about this. And it was a wonderful thing.

Nina Totenberg: And after the press conference, the sisters went out to lunch with my cousin, Elzunia, who’s Polish, who my father brought from Poland after the war and who survived the Holocaust. And she brought a bottle of vodka and shot glasses. Every day, when he finished work and teaching or whatever, he would sit down around 6:00 with some cheese and crackers and a shot of vodka and down it. And when he would go to play, he often would take a shot of vodka before he went to play. In Aspen in the summers, I remember him downing a shot on the way out the door.

Nina Totenberg: And so we sat there and we had a shot of vodka to him. It was Polish vodka. He was born in Poland, came to this country in 1937, and so we drank our shots of vodka to Roman, which is what we did at his graveside too. When we buried his ashes along with my mother, we all drank shots, and my brother-in-law poured the remaining vodka into the hole in the ground. And a darling friend of ours played some music on his cello and we said goodbye that way.

Chitra Ragavan: Where is the violin?

Nina Totenberg: Well, we promised at that press conference that we were not going to sell it to the highest bidder and have it end up in a museum or a closet or being played occasionally by somebody who was indulging himself. We wanted it to be played as it had been in concert halls all over the world, and we were finally able to do that. It took two years to restore the violin, and then it took about a year. And finally, a man in New York, I don’t know who he is, said to Rare Violins of New York, “Look, I will pay the asking price and what I want you to do is use that as a challenge to other people who are selling instruments. And I want it to be played by young artists over a period of time.”

Nina Totenberg: And it’s been, for now, given to Nathan Meltzer, who’s 19, maybe by now 20, and who has a very promising career, studies with Itzhak Perlman at Juilliard and has played now in Latin America and in Europe. And on November 15th, in Boston, he’s going to play at the Longy School of Music where my dad was for a few years the music director, and that’s where the violin was stolen, was from the Longy School of Music after a concert there. And the name of the concert is called Homecoming.

Chitra Ragavan: A beautiful story.

Nina Totenberg: Yeah, it is a beautiful story.

Chitra Ragavan: This has been a wonderful conversation. Where can people learn more about you?

Nina Totenberg: Oh, they can, I suppose, go online and read my stories. And you should read the one about the recovery of my dad’s violin, the long story. There are many stories, but the long story I think is called A Rarity Recovered or something like that. And it has pictures of my dad and the violin, and you can hear him play the violin because most of his CDs … He was 69 when it was stolen, so most of his CDs are on the Strad.

Nina Totenberg: And you could google me, I suppose, but you don’t really need to know that much about me. I’ve had a really very blessed life so far. It’s had its terrible bumps and grinds, but everybody has those. I consider myself a lucky woman.

Chitra Ragavan: Nina, thank you so much for joining us today.

Nina Totenberg: Thank you, Chitra. Chitra used to be my seatmate at NPR. It’s wonderful to have her sitting across from me again.

Chitra Ragavan: It certainly is. Thank you. Nina Totenberg is the award-winning legal affairs correspondent for National Public Radio.

Chitra Ragavan: Thank you for listening to When It Mattered. Don’t forget to subscribe on Apple podcasts or your preferred podcast platform. And if you like the show, please rate it five stars, leave a review, and do recommend it to your friends, family, and colleagues. When It Mattered is a weekly leadership podcast produced by Goodstory, an advisory firm helping technology startups find their narrative.

Chitra Ragavan: For questions, comments, and transcripts, please visit our website at Goodstory.io, or send us an email at podcast@goodstory.io. Our producer is Jeremy Corr, founder and CEO of Executive Podcasting Solutions. Our theme song is composed by Jack Yagerline. Join us next week for another edition of When It Mattered. I’ll see you then.